A Pleasure To Meet You,

Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne at Art

HK12, Hong Kong

17May - 20May 2012

Brendan Huntley speaks affectionately about his work, as

though his paintings and sculptures might have moods, emotions and

personalities of their own. As he works, he imparts his state of mind into

them, giving each one a unique character that invites a personal, emotional

response. To own one, or rather to invite one into one’s life, is to begin a

particular kind of relationship. How many of Huntley’s collectors, I wonder,

find themselves speaking to the works, offering them a greeting as they pass by

as if they embody the household gods?

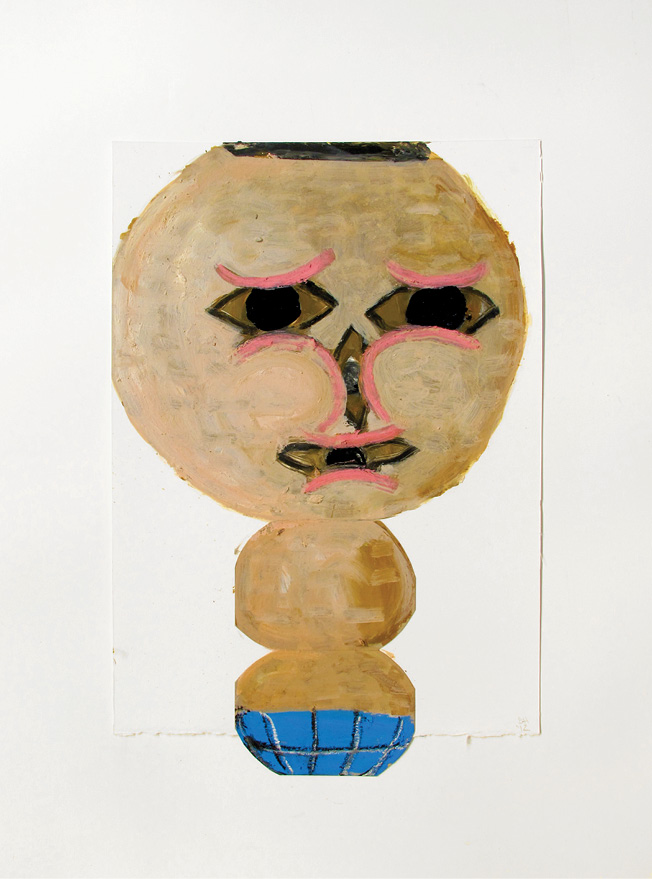

The works invite this kind of rapport because of their faces. They appeal to the human predisposition towards finding a face in anything that might suggest two eyes and a mouth in much the same way that Leonardo da Vinci famously observed that a mark on the wall could produce a landscape in the mind’s eye. Huntley’s work invites identification with appealing eyes and also with the quotidian visual vocabulary he uses, the shapes of domestic vessels and the patterns of particular fabrics. He finds the unexpected in the familiar, which is to say that there is an element of the uncanny in what he does, putting life into inanimate objects like Hans Christian Andersen in his tales where household goods act out narratives in empty rooms.

The works emerge out of Huntley’s subconscious with their own agency; he speaks of them as though they act upon him as much as he acts upon them, as though he is their medium as much as the clay, oil stick, enamels and pastel are his. Sometimes he coerces them into the form that he wishes, or at others they take shape in their own way. Lately he has begun to embrace the occasional accidents that happen as he works, recuperating the failures rather than letting them go. Certain works bear the trace of an initial but discarded position for the eyes, as though Huntley realised that the first placement did not awaken them correctly, as the saying goes, eyes are the windows to the soul. Whether, in positioning the eyes, he uncovers the latent souls of his artworks or creates them himself, it is in these apertures that their life force seems to be contained. Before any appraisal of colour, form or texture can be made, you must let them look you in the eye.

Huntley says that he feels safe with his works, even if he finds odd ones a challenge to be near. That is the nature of the company of others, of course. Each work is an individual – occasionally Huntley might recognise in one the traits of people he knows – but while the same character might often appear as both a drawing and a sculpture, this is never in the conventional relationship of a sketch to a completed work and it is as likely to appear first in one medium as in the other. Both modes of making have equal status and Huntley’s method is intuitive and improvisatory rather than plotted out in advance. Painting and sculpture offer different ways for the characters to emerge but they also offer similarities, their respective media reaching out to meet each other, the collage elements and layering of enamel and oil stick of one resembling the hand-building and application of coloured slips and glazes of the other.

A sculptor who uses ceramic techniques rather than a ceramicist, Huntley transgresses the rules of classic pottery to attempt things, such as grafting terracotta and porcelain clays, which ought not to emerge successfully from the kiln. Huntley has derived the forms of his paintings and sculptures from domestic vessels for a number of years, which is evident in the handle-like ears and noses and the tops of heads that appear to have been neatly cut from the wheel. The characters are taking on more of their own shape, however; retaining their familiar origins but growing ever more imaginative. His composites of identifiable ‘found’ forms are becoming more ambitious and now, for the first time, Huntley has made heads that scarcely resemble pots at all. Brendan Huntley makes vessels that contain an aura; he conjures out of oil stick and clay artworks that have presence and individuality, that invite you into a relationship with them and hold a promise of companionship. As he says, ‘They can bring you good vibes.’

The works invite this kind of rapport because of their faces. They appeal to the human predisposition towards finding a face in anything that might suggest two eyes and a mouth in much the same way that Leonardo da Vinci famously observed that a mark on the wall could produce a landscape in the mind’s eye. Huntley’s work invites identification with appealing eyes and also with the quotidian visual vocabulary he uses, the shapes of domestic vessels and the patterns of particular fabrics. He finds the unexpected in the familiar, which is to say that there is an element of the uncanny in what he does, putting life into inanimate objects like Hans Christian Andersen in his tales where household goods act out narratives in empty rooms.

The works emerge out of Huntley’s subconscious with their own agency; he speaks of them as though they act upon him as much as he acts upon them, as though he is their medium as much as the clay, oil stick, enamels and pastel are his. Sometimes he coerces them into the form that he wishes, or at others they take shape in their own way. Lately he has begun to embrace the occasional accidents that happen as he works, recuperating the failures rather than letting them go. Certain works bear the trace of an initial but discarded position for the eyes, as though Huntley realised that the first placement did not awaken them correctly, as the saying goes, eyes are the windows to the soul. Whether, in positioning the eyes, he uncovers the latent souls of his artworks or creates them himself, it is in these apertures that their life force seems to be contained. Before any appraisal of colour, form or texture can be made, you must let them look you in the eye.

Huntley says that he feels safe with his works, even if he finds odd ones a challenge to be near. That is the nature of the company of others, of course. Each work is an individual – occasionally Huntley might recognise in one the traits of people he knows – but while the same character might often appear as both a drawing and a sculpture, this is never in the conventional relationship of a sketch to a completed work and it is as likely to appear first in one medium as in the other. Both modes of making have equal status and Huntley’s method is intuitive and improvisatory rather than plotted out in advance. Painting and sculpture offer different ways for the characters to emerge but they also offer similarities, their respective media reaching out to meet each other, the collage elements and layering of enamel and oil stick of one resembling the hand-building and application of coloured slips and glazes of the other.

A sculptor who uses ceramic techniques rather than a ceramicist, Huntley transgresses the rules of classic pottery to attempt things, such as grafting terracotta and porcelain clays, which ought not to emerge successfully from the kiln. Huntley has derived the forms of his paintings and sculptures from domestic vessels for a number of years, which is evident in the handle-like ears and noses and the tops of heads that appear to have been neatly cut from the wheel. The characters are taking on more of their own shape, however; retaining their familiar origins but growing ever more imaginative. His composites of identifiable ‘found’ forms are becoming more ambitious and now, for the first time, Huntley has made heads that scarcely resemble pots at all. Brendan Huntley makes vessels that contain an aura; he conjures out of oil stick and clay artworks that have presence and individuality, that invite you into a relationship with them and hold a promise of companionship. As he says, ‘They can bring you good vibes.’

© Brendan Huntley 2024