How Do You Do, Tolarno Galleries, Basel HK

22 May - 26May 2013

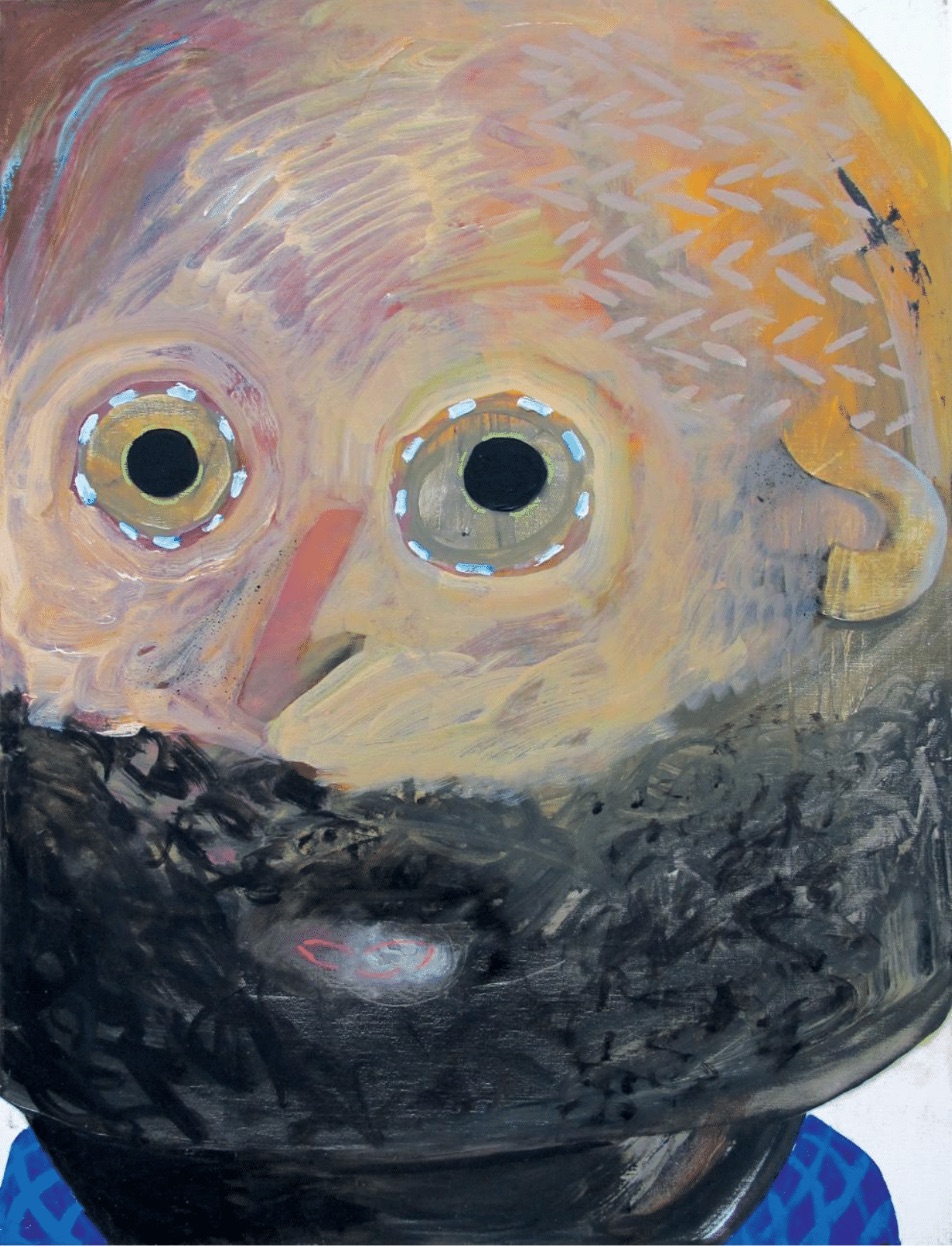

Untitled 2012-2013

Oil on linen, framed

83 x 63 cm

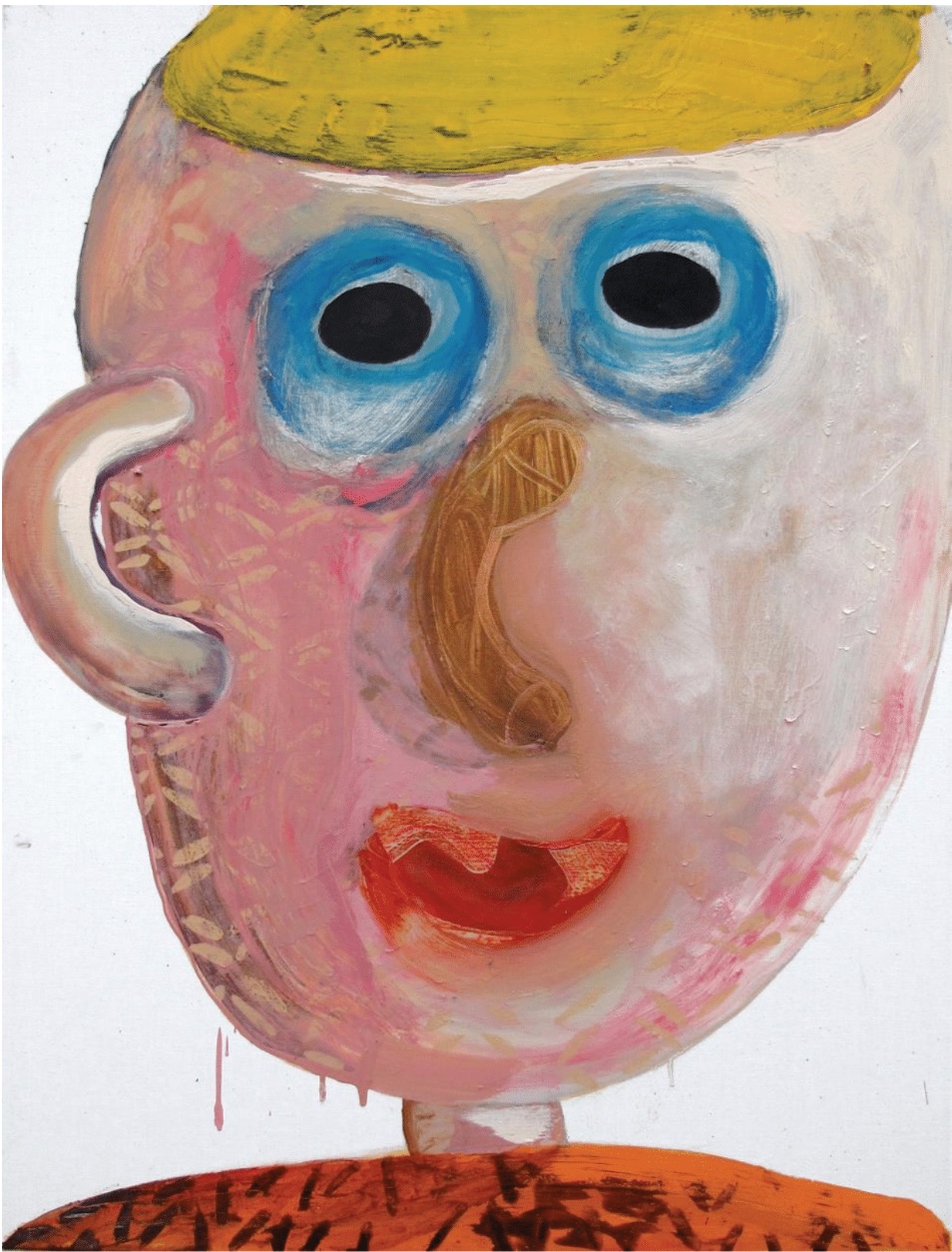

Untitled 2012-2013

Oil on linen, framed

83 x 63 cm

Untitled 2012-2013

Oil on linen, framed

83 x 63 cm

Untitled 2012-2013

Oil on linen, framed

83 x 63 cm

Untitled 2012-2013

Oil on linen, framed

83 x 63 cm

Untitled 2012-2013

Oil on linen, framed

83 x 63 cm

Untitled 2012-2013

Oil on linen, framed

83 x 63 cm

Untitled 2012-2013

Oil on linen, framed

83 x 63 cm

Untitled 2012-2013

Oil on linen, framed

83 x 63 cm

Untitled 2012-2013

Oil on linen, framed

83 x 63 cm

Untitled 2012-2013

Oil on linen, framed

83 x 63 cm

Untitled 2012-2013

Oil on linen, framed

83 x 63 cm

Untitled 2012 - 2013

Stoneware, slip and glaze and enameled wooden bats

46

x 26 x 30 cm

![]()

Untitled 2012–2013

Stoneware, slip, glaze and enameled wooden bats

27x 21 x 16 cm

![]()

Untitled 2012-2013

Stoneware, porcelain, slip, glaze and enameled wooden bats

37 x 26 x 30 cm

![]()

Untitled 2012-2013

Stoneware, terracotta, slip, glaze and enameled wooden bat

33 x 30 x 31 cm

![]()

Untitled 2012-2013

Stoneware, slip, glaze and enameled wooden bats

36 x 23 x 22 cm

![]()

Untitled 2012-2013

Stoneware, porcelain, slip, glaze and enameled wooden bat

49 x 24 x 23 cm

![]()

Untitled 2012-2013

Stoneware, porcelain, slip, glazeandenameled wooden bats

47 x 28 x 23 cm

![]()

Untitled 2012-2013

Stoneware, porcelain, slip, glazeandenameled wooden bats

47 x 28 x 23 cm

![]()

Untitled 2012-2013

Stoneware, porcelain, terracotta, slip, glaze and enameled wooden bats

46 x 21 x 21 cm

![]()

Untitled 2012-2013

Stoneware, terracotta, slip, glaze and enameled wooden bats

43 x 26 x 31 cm

![]()

Untitled 2012-2013

Stoneware, terracotta, slip, glazeandenameled wooden bats

44 x 24 x 23 cm

![]()

Untitled 2012-2013

Stoneware, slip, glazeandenameled wooden bats

48x 23 x 19 cm

Material

and form. That’s what it comes down to. A continual engagement with these two

elements. Yes, there’s an autonomy at play here. We gather that an internal

logic is divining the path that each piece travels, art history flotsam and

jetsam being absentmindedly gathered along the way, but it all comes back to

material and form. These shapes, familiar forms like handles and cups, all

rendered at human scale, some cast from moulds his father made up to thirty

years ago, given new life and embodied in vessels that do not yield to

function; canvas counterparts watching from the walls. His mother taught him to

throw, his father taught him to paint. There’s that personal history coming to

the fore again. That’s part of it; where he grew up, the people he hung out

with, the energy of being in a gang, the distillation of being alone. External

influences, true, but in the end it’s all about the squish, the taste, the

smell, dragging that paint even further around. It’s about swimming in the mud

before stepping into a beautiful pool, knowing full well you’ re just going to

jump back into the mud later on.

Douglas Lance Gibson: It feels different to the rest.

Brendan Huntley: It’s newer. Well, it’s newer and it’s older. I worked over it. I sanded back bits of it and then totally changed it. It wasn’t doing anything for me for a bit.

DLG: I like how it escapes the frame here. That feels very unconventional. The perspective is kind of warped, like it’s being pulled out of the frame.

BH: Cool. Thanks. I like that.

I’ve grown up with clay in my hands since I was allowed to put it there…

DLG: There was a time you weren’t allowed to put it there?

BH: (Laughs) I used to eat it! (Both laugh) My parents were successful with what they did in potting. They taught it. They sold it at the markets. But I saw a lot of people come up to it and show no appreciation for it. I think, subconsciously, I made the decision that I didn’t want that audience.

DLG: With your earlier ceramic work, which referenced functional vessels more directly, were you reacting against that lack of appreciation for your parent’s work?

BH: It was literally just turning it upside down, and saying, “This isn’t a pot. You can’t use it. It’s not functional, and if you try, it won’t work. It has to be viewed as a sculpture.” The fact that I was using those forms was in homage to my parents, saying, “I’m not going to do what you guys did but I respect it.” And I do respect it. I just didn’t have any interest in being a potter. I didn’t study ceramics. The only reason I work with clay is because I was brought up with it and I love it. I love the material. I love working with it. I do have interests in sculpting with other materials, and maybe one day I’ll incorporate them. I slowly am. There’s been linen, glass, and now there’s wood, but again that’s more in homage to the past.

DLG: Which leads on to the notion of the domestic present in your work, with the doilies and plinths resembling bedroom drawers. It all feels very middle-class suburban family. Now you’re presenting sculptures on bats, which are commonly used when throwing clay on a wheel, and it’s changing how you view them. They are no longer on display in a home. They are items being worked on in the studio.

BH: Yeah. It’s moved downstairs to the studio, to the workshop. I didn’t realise that’s what was happening but that’s where it’s gone: downstairs. Upstairs was the kitchen, the bedside tables, draws and the placemats. My mum would place any kind of ornamental object on a placemat. Sometimes she’d stack up a couple of placemats, make something of it. I don’t think she even realised she was doing it but it was something I picked up on, and I thought that could be a nice way to continue that idea.

I love things that you want to eat or touch or squish between your hands. It’s almost like you’re in a soap shop, and you want to touch the soap and then you want to eat it, and you know it’s not going to taste good! But it’s just that love of putting down a brush and dragging that paint along the canvas, and when I found mediums that allowed me to pull the brush even further around, it was just like I was swimming, y’know. Before I was swimming in mud, now I’ve just stepped into a beautiful pool. But I still enjoy going back to the mud a little bit.

DLG: Do you ever feel lonely when you’re painting?

BH: Not when some of them are facing me. It’s like having my own gang.

DLG: Though it feels like you’re working less with groups in your work and focussing more on individuals.

BH: That’s true. This whole series of work I’ve been building on the strength of the one, of one character, and them being individuals. Maybe that’s also in my life right now, I’ve been feeling quite independent. I’m thirty now and it’s the first time I’m feeling quite secure in being me, being human and in this world and not being too fussed on what it all means. I really like it. Maybe that’s what it is, just focussing on the individual and learning more about myself through these works.

DLG: We’re not seeing the whole form anymore. I think what cropping through the figure achieves is a sense of motion. The lens coming in tighter. The motion of the lens zooming in.

BH: Yeah. If you were out in a crowd and you were taking photos of people, that’s how I would see them. More than, say, “Sit down, I’m going to take your portrait.” I see them more as people in a crowd, or people in the street or on a tram, passing by.

DLG: They enter and leave your frame of view.

BH: That’s the other thing, you know, you can never really explain what you mean about your work. I don’t think I’ll ever understand why I make this work or why I’m even an artist. I know I’m an artist because I want to make things. I could be a carpenter but I don’t think I’d get the same joy. I love sharing these things with people. I might make a shelf at home to put some mugs on and I’ll sit back, I’ll look at it and I’ll feel very satisfied about it but maybe people aren’t interested in the shelf. (Laughs) Say with Morandi, he relates best with a still-life. With a jug. He loves the forms, he loves moving them around, and he probably just loves painting and having his excuse to paint. That’s what I think is the best thing is when you see an artist and they’ve got their excuse to work. I care a lot about stuff, like things, people, “Why is that person there? What are they doing? Where are they going?”

DLG: That comes through in the paintings, in how they are beginning to feel more observational.

BH: That’s it, I’m an observer. I’m a real people watcher. I’m a voyeur.

DLG: A peeping tom?

BH: I could easily be a peeping tom. (Both laugh) There’s a moment in the movie Honey, I Shrunk The Kids where the girl is dancing with a broomstick and the next door neighbour is looking through the window at her, and she doesn’t know. It’s this moment where he falls in love with her and she catches him catching her. It’s that moment just before someone is caught.

Douglas Lance Gibson: It feels different to the rest.

Brendan Huntley: It’s newer. Well, it’s newer and it’s older. I worked over it. I sanded back bits of it and then totally changed it. It wasn’t doing anything for me for a bit.

DLG: I like how it escapes the frame here. That feels very unconventional. The perspective is kind of warped, like it’s being pulled out of the frame.

BH: Cool. Thanks. I like that.

I’ve grown up with clay in my hands since I was allowed to put it there…

DLG: There was a time you weren’t allowed to put it there?

BH: (Laughs) I used to eat it! (Both laugh) My parents were successful with what they did in potting. They taught it. They sold it at the markets. But I saw a lot of people come up to it and show no appreciation for it. I think, subconsciously, I made the decision that I didn’t want that audience.

DLG: With your earlier ceramic work, which referenced functional vessels more directly, were you reacting against that lack of appreciation for your parent’s work?

BH: It was literally just turning it upside down, and saying, “This isn’t a pot. You can’t use it. It’s not functional, and if you try, it won’t work. It has to be viewed as a sculpture.” The fact that I was using those forms was in homage to my parents, saying, “I’m not going to do what you guys did but I respect it.” And I do respect it. I just didn’t have any interest in being a potter. I didn’t study ceramics. The only reason I work with clay is because I was brought up with it and I love it. I love the material. I love working with it. I do have interests in sculpting with other materials, and maybe one day I’ll incorporate them. I slowly am. There’s been linen, glass, and now there’s wood, but again that’s more in homage to the past.

DLG: Which leads on to the notion of the domestic present in your work, with the doilies and plinths resembling bedroom drawers. It all feels very middle-class suburban family. Now you’re presenting sculptures on bats, which are commonly used when throwing clay on a wheel, and it’s changing how you view them. They are no longer on display in a home. They are items being worked on in the studio.

BH: Yeah. It’s moved downstairs to the studio, to the workshop. I didn’t realise that’s what was happening but that’s where it’s gone: downstairs. Upstairs was the kitchen, the bedside tables, draws and the placemats. My mum would place any kind of ornamental object on a placemat. Sometimes she’d stack up a couple of placemats, make something of it. I don’t think she even realised she was doing it but it was something I picked up on, and I thought that could be a nice way to continue that idea.

I love things that you want to eat or touch or squish between your hands. It’s almost like you’re in a soap shop, and you want to touch the soap and then you want to eat it, and you know it’s not going to taste good! But it’s just that love of putting down a brush and dragging that paint along the canvas, and when I found mediums that allowed me to pull the brush even further around, it was just like I was swimming, y’know. Before I was swimming in mud, now I’ve just stepped into a beautiful pool. But I still enjoy going back to the mud a little bit.

DLG: Do you ever feel lonely when you’re painting?

BH: Not when some of them are facing me. It’s like having my own gang.

DLG: Though it feels like you’re working less with groups in your work and focussing more on individuals.

BH: That’s true. This whole series of work I’ve been building on the strength of the one, of one character, and them being individuals. Maybe that’s also in my life right now, I’ve been feeling quite independent. I’m thirty now and it’s the first time I’m feeling quite secure in being me, being human and in this world and not being too fussed on what it all means. I really like it. Maybe that’s what it is, just focussing on the individual and learning more about myself through these works.

DLG: We’re not seeing the whole form anymore. I think what cropping through the figure achieves is a sense of motion. The lens coming in tighter. The motion of the lens zooming in.

BH: Yeah. If you were out in a crowd and you were taking photos of people, that’s how I would see them. More than, say, “Sit down, I’m going to take your portrait.” I see them more as people in a crowd, or people in the street or on a tram, passing by.

DLG: They enter and leave your frame of view.

BH: That’s the other thing, you know, you can never really explain what you mean about your work. I don’t think I’ll ever understand why I make this work or why I’m even an artist. I know I’m an artist because I want to make things. I could be a carpenter but I don’t think I’d get the same joy. I love sharing these things with people. I might make a shelf at home to put some mugs on and I’ll sit back, I’ll look at it and I’ll feel very satisfied about it but maybe people aren’t interested in the shelf. (Laughs) Say with Morandi, he relates best with a still-life. With a jug. He loves the forms, he loves moving them around, and he probably just loves painting and having his excuse to paint. That’s what I think is the best thing is when you see an artist and they’ve got their excuse to work. I care a lot about stuff, like things, people, “Why is that person there? What are they doing? Where are they going?”

DLG: That comes through in the paintings, in how they are beginning to feel more observational.

BH: That’s it, I’m an observer. I’m a real people watcher. I’m a voyeur.

DLG: A peeping tom?

BH: I could easily be a peeping tom. (Both laugh) There’s a moment in the movie Honey, I Shrunk The Kids where the girl is dancing with a broomstick and the next door neighbour is looking through the window at her, and she doesn’t know. It’s this moment where he falls in love with her and she catches him catching her. It’s that moment just before someone is caught.

© Brendan Huntley 2024